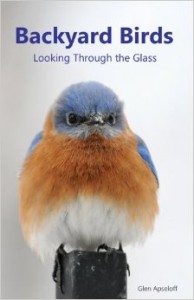

A splendid little book for new birdwatchers

Backyard Birds: Looking Through the Glass available at Amazon

Many people start looking at birds in their backyards. The process of going beyond just feeding the birds to actually watching them and learn what they are, as well as get familiar with their habits, is what takes the bird-feeder to the next level to become a bird-watcher. Some, especially today in the digital camera age, also become bird photographers in the process. Millions of people go through this process every year. Glen Apseloff of Ohio describes the process in a lovely new book called Backyard Birds -Looking Through the Glass.

The book is illustrated with 125 amazing photographs of birds which regularly occur at feeders in Eastern and Midwest US/Canada, so it can easily be used as a birdfeeder field guide. I especially like how all species are presented with descriptions of the habits of each, how to separate the sexes, what kind of seeds they prefer and any natural history or trivia connected to the species. At the end of the book, there is also a mammal bestiary visiting the feeders as well as some common butterflies in the garden. All photographs are shot from inside Glen’s house through the window.

Glen sent me a copy to review some time ago, but rather than giving you only my opinion, I want to publish a few extracts of the book. In this first part is the introductory text how Glen got into it. He was not a birder when he started this project, but he is now. Sit back and enjoy!

…………………………………………….

Through the Looking Glass – Inside-Out

Every photograph in this book was taken from inside my house (in Powell, Ohio) through a closed window. This in part explains the title: Looking Through the Glass. But the title is intended to mean more than that. For most of my life, I viewed windows as simply something to let in light. I didn’t appreciate what was on the other side. I do now.

The title of this book is also a play on words of Lewis Carroll’s literary work, and it’s a metaphor. When Alice stepped through the looking glass, she entered a place of wonder. When I look through the windows of my house, I too experience that, and when you read this book, I hope the same thing happens to you.

The baseball player Yogi Berra once said, “You can observe a lot just by watching.” Until recently, I didn’t do that, and I didn’t notice much around me. I had no clue how many species of birds could be found in my own backyard, and I didn’t know enough to distinguish one from another if they looked even remotely alike. To me, a sparrow was a sparrow. Not a song sparrow or a field sparrow or a house sparrow or a chipping sparrow. Just a sparrow. I had grown up with cardinals in the neighborhood (they’re the state bird of Ohio), but I never wondered how a juvenile of that species differed from an adult, or how juveniles of any species differed from adults. I had also never noticed that birds molt, and I never gave any thought to possible differences between winter and summer plumage, let alone the transition between the two. I’ve since learned the basics, or at least some of them, from books and from the internet, including web sites of state departments of natural resources, the Audubon Society, and the All About Birds site of Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The information I provide in this book is from those sources.

Winter wildlife in my backyard

Eastern Bluebird looking fluffy..

Glen writes: In the cold of winter, as shown here,

bluebirds frequently fluff their feathers to trap air between the

feathers and their body, for added insulation.

Until a couple of years ago, I believed central Ohio was relatively devoid of wildlife. With that misconception in mind, I traveled widely to photograph animals as far away as Madagascar, Botswana, New Zealand, Alaska, and even Antarctica. Usually I hired guides, and they showed me local fauna in natural settings, sometimes with stunning backdrops—the jungle, the ocean and mountains, glaciers. I never imagined that anything in Ohio could compare to that, to lemurs hanging from trees, or penguins jumping off icebergs. Certainly nothing in my own backyard could compare. But then a couple of years ago I faced an extended period without a vacation. As weeks turned into months, and one season into the next, I felt increasingly compelled to take out my camera and photograph something. Anything.

That’s when I thought of what I might be overlooking. Backyard birds? Maybe, but how many birds can people really see in their own backyard? When I go to art festivals and find photographs of what look like backyard birds, the photographers invariably tell me they took the pictures in a state park or some other out-of-the-way place. Of course, people really do take pictures in their own backyards, but the best photographs I’ve seen have always been somewhere else.

So what about my backyard? Could I photograph anything there? I had serious doubts. Especially in the winter. It isn’t like Antarctica where you can just sit down and penguins waddle up to you and peck at your parka.

One thing I knew was that I did not want to spend a lot of time outside in the winter. The last time I did cold-weather photography, I thought I might get frostbite and cause permanent damage to my fingers, despite chemical hand warmers inside my gloves. I don’t mind sacrificing time, money, and comfort to photograph wildlife, but I draw the line at body parts.

Looking out the window for birds

However, outdoor photography typically takes place outdoors, and if it’s done in the winter, that means going out in the cold. Or does it? Instead of photographing birds the way countless other photographers do, by going out and finding them, what if I just stayed inside and waited for the birds to find me?

That’s how I came up with the idea for this project. One of my objectives with wildlife photography has always been to give people a better appreciation of nature. By photographing birds from inside my house, I could show others what they’re missing around them, and maybe I could motivate them to want to see more and to learn more. I could show people that working long hours and seeing daylight primarily through the windows of an office building or a house isn’t an excuse to ignore nature. I could show them that all they have to do is look outside. This was assuming, of course, that I could find birds to photograph.

With that goal in mind, I embarked on this project. It started as a calendar, not a book—a calendar of backyard birds photographed from inside my house, through closed windows. I wasn’t sure I could find a dozen different species, but I figured I could include pictures of both males and females for those that are sexually dimorphic, and then I might need as few as half a dozen. Eventually I should be able to find that many.

I used a handheld camera (no tripod or cable release for remote pictures) with no special filters, not even a polarized filter, and no flash. I wanted to show what people can see if they simply look outside their windows. I removed a couple of screens, put up decals to try to minimize the likelihood that birds would fly into the glass, and then I started observing. Because it was winter, with no plants to attract birds, I put out suet and bird seed in feeders on my back deck and experimented with different types. I learned that most birds seemed to prefer peanut-butter suet (especially with large pieces of peanuts) and definitely black-oil sunflower seeds. Many birds were also attracted to safflower seeds, and the smaller birds (including finches, buntings, and chickadees) seemed to prefer a mix of finch food with millet and sunflower seeds.

Like other full-time workers anywhere, I could find only limited opportunities to watch and photograph birds. I’ve never been good at standing still for extended periods, but I forced myself to spend time at the windows, and not just the ones with a view of the back deck. I began looking out the bathroom windows, the dining-room windows, and even the little panes of glass alongside my front door.

I’m seeing birds

My wife, Lucia, bought a book called Birds of Ohio Field Guide by Stan Tekiela, and I looked at the pictures to identify birds I saw outside. When I first flipped through the pages, I couldn’t believe such a wide variety of birds lived in Ohio. The book described more than a hundred of them, and in the introduction, the author mentioned that more than 400 different species have been recorded in Ohio. I found that especially difficult to believe. But then, after I started this project, everything changed. I began seeing birds— unusual and even exotic ones—through my windows: brilliant blue indigo buntings and other species that I thought existed only in the tropics, such as the scarlet tanager. I was amazed by how many birds I observed “just by watching.” Close to half of them, I had never seen in my life—northern flickers, ruby-throated hummingbirds, cedar waxwings, and a rose-breasted grosbeak, to name a few. Others I had seen but had never really noticed, like the multicolored iridescent European starlings that I had always thought were simply gray and black.

In an attempt to show people what they can see just by looking through their windows, I discovered what I had been missing for years, actually for decades. In this book, I’ll show you what that was. I’ve arranged the birds in alphabetical order by common name (e.g., “bunting, indigo” precedes “robin, American”) for lack of a better system. Whenever I introduce a bird, the name is in bold print. The first entry is a blackbird, more specifically a red-winged blackbird.

—————————————————————————————–

Glen’s book will soon be distributed (on trial) in Barnes and Noble bookstores, but Backyard Birds: Looking Through the Glassis also available at Amazon.

Glen Apseloff is an award-winning landscape/wildlife photographer who has traveled on all seven continents to capture unique images in nature. His photographs have been published in several calendars and print magazines. He also has photographs in the Kent State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives. He lives in Powell, Ohio, with his wife, Lucia; dogs, Poco, Tiki, and Gucci; and cat, Pelusa.

The next post will be dealing with How to take photographs and provide a safe environment for the birds.

——————————————————————————————————–

If you liked this post, please consider sharing it with your friends, on mailing lists you belong to, on Twitter, on Google+, on your Facebook wall, and on Facebook groups and on Pinterest. Or you may blog about this blog.

Finally, subscribe to this blog, not to miss any future posts.

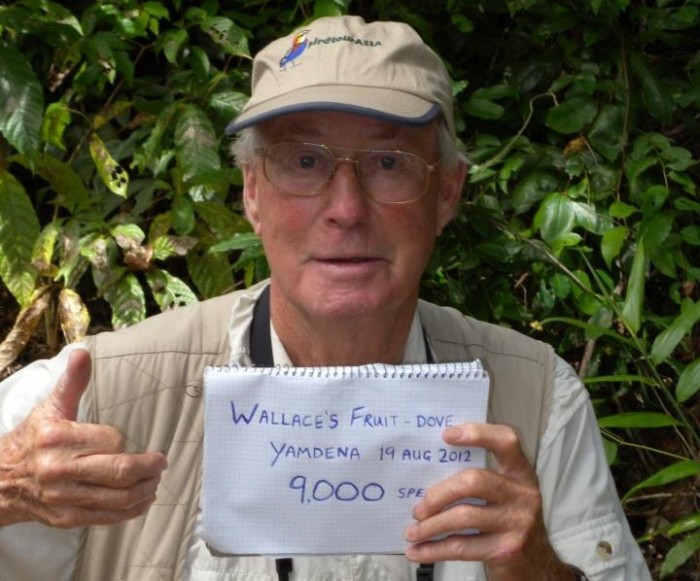

![IMG_3777-L[1]](https://birding.com.co/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/IMG_3777-L1.jpg)